Main Guide

Japanese Learning Guide

- Learn kana

- Setup Anki and Yomitan

- On the topic of isolated kanji study

- Learning basic grammar and vocabulary

- Consuming native context

- Further output

- Writing kanji

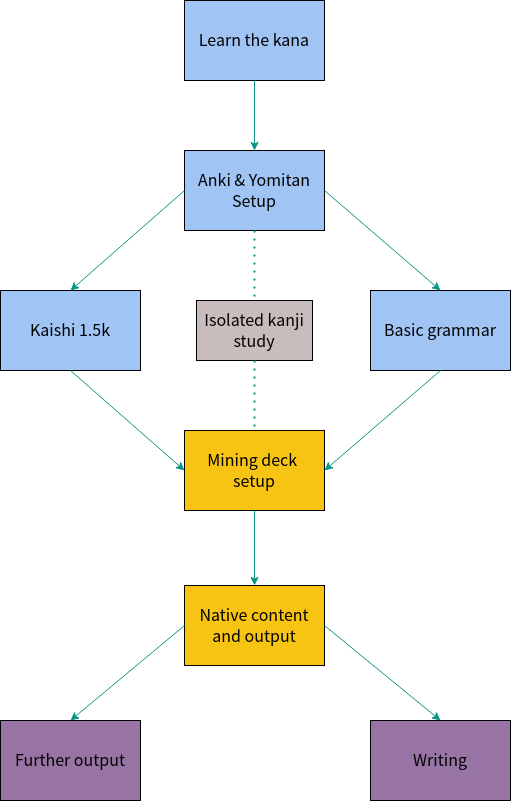

In this section, I give a flowchart you can follow to learn Japanese. Each step of the way, I explain what you should be doing to get to the next stage. If you would like a deeper, more technical explanation of what input-driven immersion-based language learning is, please see this section.

How then should one go about learning Japanese? There have been multiple guides written discussing this exact issue that you can read in the resources page. In this section, I would like to propose a simple Japanese learning roadmap.

By far the longest step will be consuming native Japanese content, but it's also the one that should be most fun to you, considering that you're the one choosing what media you consume. Let us break down each of these steps one by one.

Learn kana

Japanese technically has four main scripts it uses.

- Hiragana (平仮名)

- Katakana (片仮名)

- Kanji (漢字)

- Romaji (ローマ字)

Hiragana and katakana are similar to the English alphabet, although instead of representing single letter sounds, they represent two letters sounds like ka and ri. Kanji is what most beginner think of when they think of Japanese. These are originally of Chinese origin and are used to describe words, nouns and so on. The last script isn't really a standard script, it is just the English alphabet (the Roman alphabet as the name implies.) The first scripts one learns are the first two as they represent the same sounds and are simple to learn in comparison to kanji. In contrast, you might learn new kanji for a very long time but you should know all hiragana and katakana (collectively called kana). You can learn to write them too if you'd like, but unless you practice often you'll eventually forget how to write them, even if you can tell how to read them.

The first thing you should do is read Tae Kim's guide from here to here in order to make sure you actually understand how writing works in Japanese. After this, use this game.

Setup Anki and Yomitan

This section is technical and takes a long time so you can find a detailed explanation on this page. The basic tools we will use are a spaced-repetition system called Anki and an interactive online look-up dictionary manager called Yomitan. Anki uses Anki decks, collections of flashcards to help you remember things, and it is usually those decks that will contain the bulk of our language learning.

On the topic of isolated kanji study

It is not fully clear how useful isolated kanji study is to the development of Japanese mastery. Isolated kanji study refers to the act of studying kanji readings on their own, without studying words directly. Some people never studied kanji by itself and instead learned words using kanji directly. Some people started their Japanese journey by using a tool such as Remembering the Kanji or the Kodansha Kanji Learner's Course. I would personally advise against going through the entirety of either books, even in the form of an Anki deck. Instead, I would suggest people skip this step for now and start working through a vocabulary deck, namely Kaishi 1.5k. If the vocabulary deck is too hard, it might then be worth using the shortened form of Remembering the Kanji, usually called RRTK450. The deck can be found here. If you're the kind of person that likes learning from textbooks, I actually really like the Basic Kanji Book I and II.

Another useful tool is the kanji map website, which lets you input a kanji character and see it get broken down into radicals, the building blocks of kanji. It also allows you to see if it is used as a building block in other kanji. Learning kanji takes a long amount of time, do not get discouraged if learning Japanese feels very hard in the beginning. A lot of the difficulty in learning a language like Japanese is front-loaded: Once you learn enough words and kanji your reading experience gets much smoother. English speakers are usually discouraged at the fact that one requires learning thousands of kanji to properly read Japanese. But remember:

English too requires learning word readings!

If you're not convinced, please try to read this poem. In the first four sentences, we see the digraph gh multiple times, and it isn't read the same in every word. Effectively, English also requires learning how written words sound. Tough is not the same as though, yet both words end in ough.

Learning basic grammar and vocabulary

This first step is quite important as it will set you up for success once you start consuming a lot of native content. Some people believe you should start immersing from day one, but personally I think it's better to spend your first few weeks learning basic vocabulary and going through a basic grammar guide. But first, a few remarks:

- You do not need to have memorized the entirety of the grammar resource you're using to move on.

- You do not need to have finished your vocabulary deck to start immersing, do so whenever you feel the time is right.

- Grammar is best understood in context, i.e. in immersion, but it is still worth it to learn some grammar before you start, if anything just to know what is out there (priming) .

- Most grammar resources are flawed in some way, so if something doesn't make sense, take a look at other grammar resources to see how they present the point that is causing you trouble.

With this out of the way, let's see what grammar resources I recommend. I am currently in the process of writing my own grammar book which will become the main recommendation after it's out, but for now here are a few I like.

The grammar guide I like most is IMABI. The author understands Japanese grammar extremely well and you can find a lot of information on the website, even for classical Japanese. My only issue with IMABI is that it is quite comprehensive and extensive, and Seth, the author, believes that the best way to learn Japanese properly is to understand grammar the way linguists understand grammar. While I sympathize with this, I think many beginners will dislike this approach. Still, I suggest you check it out because it actually is worth it. No matter which grammar guide you choose to use (except maybe for IMABI), you will have to follow it up with more grammar anyway.

There are other popular guides out there. The most well-known one is Tae Kim which we have seen before when we learned what kana and kanji were. If you decide to go with this one, keep in mind Tae Kim is not a linguist, and he considerably misunderstood what the が particle does. It's a bit of a "quick and dirty" guide, and it is indeed both. Nonetheless, a fine guide to start with and what I personally used when starting out. Other similar guides worth mentioning are Sakubi (which is similar to Tae Kim) and BoiroDaisuki (which is based on sentences from visual novels). All three of these have their issues, but they will work as starting guides. If anything, I recommend you use all three at the same time. There is also Cure Dolly, and while I heavily respect what she tried doing, I don't recommend this playlist for a variety of reasons. Regardless, she has helped many people learn Japanese and I respect her work for that reason, RIP.

Regarding vocabulary, the recommended Anki deck is Kaishi 1.5k which I made (with a few people) to rectify the problems with Tango and Core2.3k. I highly recommend going through a phonetics deck at the same time. Phonetic radicals are the part of kanji that indicate sound and learning them can be very useful to read new, unfamiliar kanji. It is not an exact science most of the time, but it is still worth learning. You can do the phonetics deck before or after Kaishi 1.5k.

Consuming native content

If you're done with Kaishi 1.5k (or well on your way) and you have some grammar under your belt, give yourself a pat on the back. You probably feel like you still don't know any Japanese. That's normal. You haven't really acquired much Japanese yet, but you have learned a good deal. It is now time to start the real journey. This step never technically ends as you will hopefully keep consuming Japanese content as you get better and better at the language. The main aspect of this section is to setup a mining deck. A mining deck is an Anki deck you create yourself using Yomitan on content that you read (or potentially watch with subtitles) where you "mine" words from sentences you see in the wild.

Creating a mining deck is a topic that deserves a thorough explanation and this task is undertaken on the mining page. I also recommend you start listening to Japanese actively as soon as you can. As said previously, media recommendations can be found on this page. Find a medium you like, be it anime, visual novels or Japanese TV and start listening. Do not be surprised if your ability to listen is wildly inferior to your ability to read at first. When reading you have a written support you can look at any time. Kanji provide some meaning and help you read. If possible, try to find native speakers to output with. It's fun and motivating.

At this stage of the journey, it would be useful to consult some more advanced grammar resources. My favorite one is the Dictionary of Japanese Grammar. The way I would study grammar is by doing the following:

- Come across a sentence using unfamiliar grammar in your reading.

- Look up the grammar in this master reference.

- Note down the grammar item you have encountered in a list somewhere.

- Review it from time to time.

Another great idea if you are comfortable with Japanese definitions is to do the NihongoKyoshi anki deck you can find here. Other popular grammar resources can be found on the resources page.

More talking and writing to Japanese natives

Once you have a good grasp of the language and can read more comfortably, it's a great idea to start speaking with Japanese natives often. Likewise, I recommend you start writing in Japanese (not necessarily physically of course) and have people correct you. This is not to say you cannot start output much earlier. If you have the opportunity to output earlier, do it and try to get corrected as often as possible, because getting good at reading is not enough to get good at writing, and likewise getting good at listening is not enough to get good at speaking. You need to actually produce (what we call output) and work in the language with others.

On the topic of writing kanji

Many Japanese learners are surprised to hear that a lot of people do not consider writing kanji physically to be important. In this day and age, most people interact with Japanese online or while speaking, very rarely do they have to write kanji explicitly. If you are interested in learning how to write, I highly recommend reading this guide. The best way to learn how to write in my opinion is to follow the Kanken deck found here. This deck will go up to Kanken level 2, which covers all the so-called 常用漢字 jouyou kanji, the kanji characters designed as common use by the Japanese Ministry of Education. These kanji characters are usually not the only ones you will see when reading, but knowing how to write all of these is already a tremendous achievement. In a street interview video, YouTuber That Japanese Man Yuta interviewed native Japanese people and many of them forgot how to write certain characters.

What's next?

Whatever you want. Go take the JLPT N1 if you'd like, it's a nice achievement and you get recognized for your efforts. If you're really motivated and want to learn even more, try to pass the Kanji Kentei. I discuss certifications in this section. You are now free to do whatever you want and enjoy the language in ways you would have never imagined!

Checklist

Here's a simple checklist of things you should do, in order:

- Learn kana.

- Finish a first vocabulary deck and grammar resource.

- Setup Anki and Yomitan properly, including a mining deck.

- Get input and mine from Japanese content and try to get output with natives.

- If desired, learn how to write kanji.